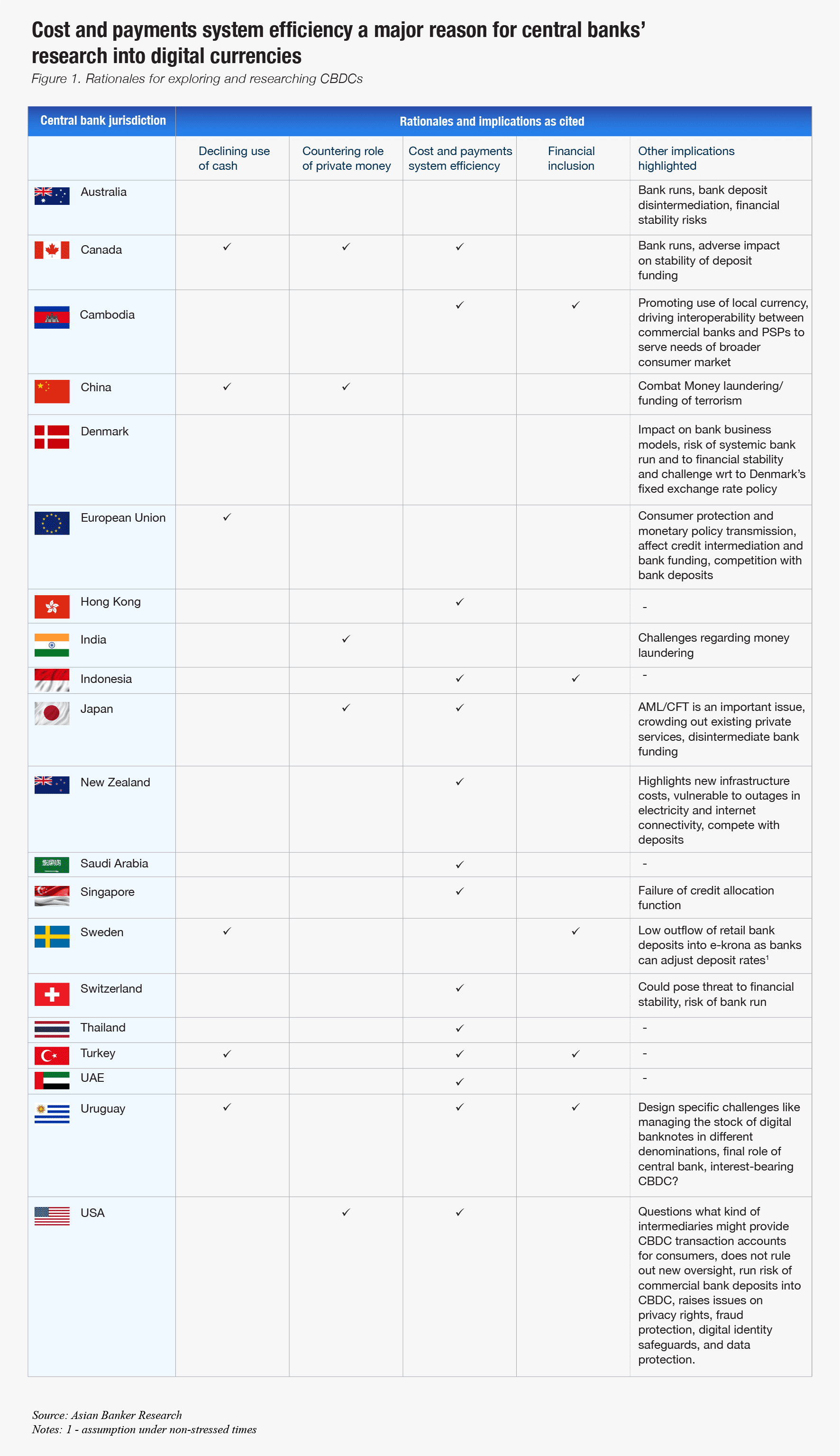

- There is a renewed interest by policymakers in advancing digital currencies research as a means to create reliable payment infrastructure

- Despite non-homogenous adoption of digital payments in the region, Asia’s central banks are quicker to explore the commercialisation of their digital currency plans

- Notwithstanding CBDC benefits, concerns around structural model, technology and probable disintermediation of commercial banking system remain unresolved

The pandemic may well serve as a catalyst for the shift to agile and accessible payment infrastructures, putting central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) into sharper focus. The crisis does not only make the case for payment architectures to withstand greater pressure from the explosion of digital payments as the preferred choice, but also necessitates broader accessibility of contactless payments for targeted groups as well as the more efficient distribution of stimulus funds.

“Cash usage is declining precipitously, and COVID-19 and the attendant rise of e-payments are likely to boost CBDC development across the globe”, said Benoît Coeuré, head of Bank of International Settlements (BIS) Innovation Hub.

%20Innovation%20Hub.jpg)

Benoît Coeuré, Head of Bank of International Settlements (BIS) Innovation Hub

Richard Byworth, CEO, Diginex

The crisis has also amplified calls for policymakers to step up their efforts in advancing CBDC research to create reliable payment instruments for transacting in the digital economy. “What was generally perceived to be explored from a theoretical potential, the rush to implement now can ultimately supersede exploration of CBDC archetypes as conduits for the disbursement of stimulus packages, the renewed interest by policymakers is fast tracking the advance of this space”, highlighted Richard Byworth, CEO of Diginex, a digital financial services and blockchain solutions company that partners with various stakeholders to make digital assets more accessible.

Notably, central banks in Asia appear to be fairly ahead of their Western counterparts in their digital currency plans. This comes despite the lack of homogeneous adoption and transition of different countries at different pace towards digital payments within the region. Asia has unequivocally emerged as the world’s largest market for consumer digital finance with China alone comprising half of its transaction value. “The digital payment transaction value in Asia is expected to increase from $2.9 trillion in 2020 to $5.1 trillion in 2024, comprising more than 60% of value by market”, estimated a DBS report on digital currencies titled “Digital Currencies: Public and Private, Present and Future”.

Despite popularity, private and decentralised forms of money lack broader acceptability

The sheer pace and scale of transformation in retail payments has encouraged payment service providers (PSPs), credit card companies and technology firms to challenge bank-based payment systems. Several new forms of private money backed one for one by central bank liabilities – either cash or reserves – have shown significant traction. Among these, electronically stored value facilities or e-money wallets such as AliPay and WeChat Pay in China, PayTM in India and M-Pesa in Kenya are have gained widespread acceptance. Key private players of the Chinese payment system, AliPay and WeChat Pay that account for 90% of local retail payments market have sought expansion to customers in South-east Asia.

The private sector has also joined the digital payments bandwagon, rallying behind cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin, Ethereum and Ripple. However, these cryptocurrencies fail to fulfil basic requisites of money, as they are not widely accepted as a means of payment and tend to be volatile in their valuations. Moreover, their usage remains minimal on account of jurisdictional bans, compliance and limited understanding of risks involved in their usage.

The announcement of Facebook-backed digital currency Libra attracted a lot of attention, although not all positive. In its initial whitepaper, the multi-currency Libra Coin initially intended to stabilise its value by anchoring to a basket of safe assets, i.e. bank deposits and government securities held in the administered Libra Reserve. This raised key concerns among regulators regarding Libra’s potential to interfere with monetary policy and governments’ sovereign rights, should the network reach significant scale and volume of domestic payments. “The concept of a CBDC had been developing within the walls of central banks across the globe over the past year, and while Libra of course catalysed a more proactive response, pandemic induced economic crisis has really kicked deliberations into high gear,” added Byworth.

In response, Libra released its revised whitepaper in April this year, citing that it “incorporates actionable improvements into the economic design of the Libra network.” The new approach augments the Libra network by including single-currency stablecoins, each of them tied on a 1:1 basis to various fiat currencies (e.g., LibraUSD, LibraEUR, etc.) This essentially means that each stablecoin will be fully backed by the Reserve, comprising cash or cash equivalents and very short-term government securities denominated in that currency.

The paper also introduces Libra Coin to be a digital composite of the single-currency stablecoins, the value of which will be defined in fixed nominal weights such as special drawing rights (SDRs) issued by the International Monetary Fund (IMF). This approach raises hopes for CBDCs (as and when they are launched) to be directly integrated with Libra, removing the need for its network to manage the associated Reserve. Put simply, this means a complete replacement of the single-currency stablecoin by the CBDC.

However, the project remains in limbo as it fails to pass the regulatory tests of financial stability and trust. More importantly, it lacks the credibility of a national currency backed by an authorised central bank.

“Libra won’t be sustainable without the support and supervision of central banks,” highlighted Mu Changchun, deputy director of the People’s Bank of China’s (PBOC) payments department. “The central bank’s research team had tested Libra’s code and found it’s still in an initial stage and the quality of the code isn’t stable for high concurrent retail transaction scenarios,” he added.

%20payments%20department.jpg)

Mu Changchun, Deputy director payments department, People’s Bank of China

Hyun Song Shin, Economic adviser and head of research, BIS

Can CBDCs overcome the shortcomings of cryptocurrencies?

It is with this rationale – and also in part to determine who would control the future of money – that central banks are experimenting and researching new CBDCs to replace or complement cash, enhance payment infrastructure efficiencies or broaden financial inclusion. “Apart from increased safety and efficiency for end users, CBDCs could improve financial inclusion in countries where a sizable portion of the population does not participate in the formal financial system”, stated the DBS digital currency report.

The report by the Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures (CPMI) of BIS defines CBDCs as “new variants of central bank money, primarily a central bank liability, denominated in an existing unit of account, which serves both as a medium of exchange and a store of value.”Thus, a central bank-sponsored CBDC comes with prior approval of the regulator and need not be backed by assets. “While the private sector is well placed to draw on ingenuity and creativity to serve customers better, the integrity of payment systems is best done on solid central bank foundations”, added Hyun Song Shin, economic adviser and head of research at BIS. This instils much confidence and facilitates broad acceptance, as in the case of traditional paper money. “The biggest issue that cryptocurrencies have versus fiat currency right now is instability of price as speculation and leverage lead to some violent price moves. The other key factor is trust as whether it fits with political view or not, governments and their money are generally more trusted than the current landscape of cryptocurrencies”, stressed Byworth.

In a BIS survey in January 2020 covering 66 central banks, it found that 80% of central banks across the world are engaged in research and experimentation of CBDC, up from 70% in 2018. Forty per cent of central banks have progressed from conceptual research to the experiments or proofs of concept (PoC) stage, while another 10% have developed pilot projects.

Taking a collaborative approach on CBDCs to improve cross-border payment systems

Any progress on CBDCs would require substantial coordination for cross-border payments. Six central banks and BIS have formed a working group where they share their experiences as they assess the potential cases for CBDC in their respective home markets. Members of this working group include the Bank of Canada, the Bank of England (BoE), the Bank of Japan (BoJ), the European Central Bank (ECB), the Sveriges Riksbank and the Swiss National Bank. “Central banks have to put their heads together to reflect on these challenges and opportunities and they are yet to achieve a political stake, but at this stage they just want to learn from each other”, noted Coeuré as he spoke from his position as a co-chair of the working group.

The finance ministers and central bank governors of G7 also formed a working group on Stablecoins in July 2019 and published a report providing an overview of the stablecoin ecosystem, details on regulatory oversight, policy challenges and the way forward to improve cross-border payment systems.

In parallel, the ECB has assembled a taskforce of European national central banks to study the feasibility of a euro area CBDC issued in various forms, including minimisation of spill over to the commercial banking system and financial intermediation. Banque De France has called for applications to explore and identify concrete cases for integrating CBDC for interbank clearing and settlements.

In 2017, the Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA), in collaboration with HSBC and ZA Bank Limited, Hong Kong Interbank Clearing Limited (HKICL) and the R3 consortium, launched Project LionRock to study the feasibility, risks and possible benefits of wholesale CBDC. The project included a PoC study on token-based CBDC and issued debt securities into a single distributed ledger technology (DLT) system.

In August 2018, the Bank of Thailand (BoT) initiated Project Inthanon with eight financial institutions (FIs) and R3 to explore the application of DLT in enhancing Thailand’s financial infrastructure and improving the settlement system’s efficiency (wholesale CBDC). BoT is expanding research from wholesale CBDC to domestic corporate and retail levels. The CBDC prototype will be integrated into supply chain management to bring higher payment efficiency to domestic businesses. For example, KASIKORNBANK (KBank) has played an active role in BoT’s national level initiatives. As a representative of KBank to join as one of the seven steering committee members in Inthanon Project, Silawat Santivisat, Head of Transaction Banking Division noted “As part of our aspiration towards digital banking, KBank has played a prominent role as a key member in Inthanon interbank and cross-border payment infrastructure project since the beginning. The project has completed two out of three phases: interbank settlement and 3rd party fund transfer. The last phase is to conduct cross-border payment”.

Silawat Santivisat, Head of Transaction Banking Division, KASIKORNBANK

Patrick Hess, Finance Professor at Goethe University and Principal Supervisor, European Central Bank

To explore interoperability among ledgers, HKMA and BoT collaborated in May 2019 for Project Inthanon- LionRock, which studied the application of CBDCs to cross-border payments. A Thai baht-Hong Kong Dollar corridor network was designed to enable real-time cross-border transfers between two countries. The project was completed in December 2019 and a DLT-based proof-of-concept prototype was developed successfully together with ten participating banks from both countries.

The Bank of Canada and the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) conducted the first successful trial on cross-currency payments using CBDCs. The central banks linked up their respective experimental domestic payment networks, namely Project Jasper and Project Ubin using hashed time-locked contracts (HTLC) to connect the two networks and allow payment versus payment (PvP) settlement without a trusted third-party intermediary.

The Saudi Arabian Monetary Authority and the Central Bank of United Arab Emirates have announced a pilot project for common digital currency Aber, which aims to lower costs for cross-border transactions between respective countries’ financial systems. The monetary authorities intend to restrict the use of Aber to a limited number of banks in each jurisdiction, further considering economic and legal requirements, should no technical obstacles arise.

Developments in select standalone projects

Other standalone projects have gained traction too. The Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey is set to finalise the pilot of ‘digital lira’ by the end of 2020. Notably, a history of higher inflation in the paper-based Turkish lira points to online digital currencies such as cryptocurrencies being a popular way to pay for future online purchases.

The United States Federal Reserve views CBDCs to raise profound legal, policy, and operational questions. However, it has not ruled out a future collaboration with other jurisdictions as it continues to analyse the potential benefits and costs of CBDCs. Highlighting the significance of immediate access to funds, digital wallets and contactless payments, Fed has prioritised the implementation of FedNow real-time payments and settlements service. While there is no change in the target release date of 2023 or 2024, it aims to complete additional development work in phases so that the initial service can be launched expeditiously.

While the BoE has not made a decision yet on the introduction of CBDC, it intends to engage widely with stakeholders to explore benefits, risks and future practicalities. Its design features include an API access that allows private sector payment interface providers to connect to the BoE core ledger, which allows only regulated entities to participate. BoE recognises the challenges to the banking sector and the acceleration of shift towards disruptive alternatives as COVID-19 provides a thriving environment for digital-first players. “The BoE is keeping central bank digital currency research high on its 2020 agenda. It is encouraging to see that the recently appointed Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey, much like his predecessor Mark Carney, has come out as a proponent of CBDCs - acknowledging that in a few years’ time the UK will likely be heading towards some sort of digital currency solution”, said Byworth.

The rapid increase in cashless payments in many countries stoke further interest in CBDCs. Sweden bucks the trend, as cash in circulation as a percentage of GDP has decreased to one percent as of 2019, driven by favourable developments in mobile-based payment systems such as Swish. With cash use declining in Sweden, the Sveriges Riksbank is working on digital initiatives that reinforces the state’s role in the payment market. It aims to provide the general public with a value-based e-krona and envisages a “platform” where payment service providers (PSPs) of the e-krona would connect and distribute the currency. The next stage is expected to be a pilot for a prepaid value, non-interest bearing and traceable e-krona.

Banco Central del Uruguay, the central bank of Uruguay, has successfully piloted “e-Peso” between November 2017 and April 2018 to promote financial inclusion. Contrary to the use of DLT, the bank issued the distribution of unique digital bank notes in several denominations to an “e-note manager platform,” which acts an ownership register of the digital bank notes. The pilot included the issuance of 20 million e-Pesos, of which 7 million were distributed by a third-party PSP, necessarily backed by pesos in the central bank account. Peer-to-peer transfers were initiated instantly via mobile phone using text message or e-Peso application. This has moved the programme into the evaluation phase and various questions around design specific challenges are now being considered.

Asia’s digital currency plans to see faster implementation than that of West

The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) will continue to look into the pros and cons of issuing an electronic form of Australian dollar banknotes (eAUD). Although it does not have an immediate plan to issue one just yet, RBA highlights that eAUD could coexist with electronic payment systems operated by FIs. In late 2018, RBA established an in-house innovation lab which undertook a POC of a wholesale settlement system running on a private, permissioned Ethereum network.

With the launch of its backbone payment system – National Bank of Cambodia’s Bakong system provides backbone for commercial banks and PSPs of e-wallet and money transfer services to connect and communicate on single platform through an open API. This allows fund transfers to be processed on real-time basis without the need of a centralized clearing house. Bakong is built on top of the Hyperledger Iroha blockchain, a permissioned blockchain network. The application works like an e-wallet where customers deposit cash for digitised money, stored in in their bakong wallet. Communication and exchange of money is made possible between all parties that sit on same platform. The end users download Bakong wallet from application store. The system promotes financial inclusion and use of Cambodian Riel in an otherwise highly dollarized economy.

In July, BoJ assigned a new team to look more closely into the technical feasibility of digital Yen. Although there are no concrete plans to launch one yet, the new approach does reflect departure from its previous tone where it had through a working paper series, emphasised several risks from an inappropriate CBDC design. The working paper noted that CBDC’s could crowd out private-based payment instruments and thereby discourage innovation.

During the same month, MAS concluded the fifth and final phase of Project Ubin. The fifth phase explored the use of blockchain technology in commercial applications across different industries and how these applications could benefit from the integration with the prototype developed. The findings conclude successful settlement of payments in multi currencies on the prototype network and valid use of smart contracts in use cases such as delivery-versus-payment (DvP) settlement. It also includes payment commitments for trade finance. Integration with other blockchain-based platforms to enable end-to-end digitalisation across many industries was also explored.

The People’s Bank of China (PBOC) may be the closest to becoming the first to introduce a centralised digital yuan, which will be issued to select commercial banks. PBOC launched a limited trial of its centralised digital currency electronic payment (DCEP) commercially in December 2019.

China’s unique approach to CBDC

Unlike other central banks in the region, PBOC had a different mandate for its digital currency. That is, to “substitute (and not replace) cash in circulation, which is M0, rather than M2, which would avoid generating impact on credit and monetary policy transmission,” said Changchun. Thus, as a part of M0, the CBDC would share many properties with cash, nearly qualifying it as a legal tender. The digital currency would still be a liability under the central bank’s book, leaving the creditor-debtor relationship unaltered. A 1:1 backing by a fiat currency would prevent new currency to enter circulation. The design features of a two-tier system also alleviate some concerns over financial disintermediation for commercial banks. “There is a two-tier system for issuance and redemptions where on the first layer, the PBOC issues and redeems CBDC via commercial banks and on the second layer, commercial banks are responsible for re-distributing the digital money to retail market participants”, stated the DBS digital currency report. The two-tier model helps avert disintermediation as it allows commercial banks to maintain their role in consumer facing functions. “While there isn’t an official account of China’s CBDC design but we know from other official announcements that it is mainly for domestic purposes and is a central bank liability, distributed by commercial banks in China”, commented Shin. Complementing cash, the CBDC is expected to be non-interest bearing, and with subject to transaction limits and payment regulation to reduce the incentive to exchange all cash into digital Yuan.

The technical design features of DCEP gives the central bank full control over the supply and reserve of DCEP, such that it has now over the issuance of legal tender. The centralised feature vis-à-vis the decentralised ones (e.g., Bitcoin) makes the DCEP not fully anonymous. Even when compared to the centralised models that govern the traditional e-payment systems, the circulation of CBDC by contrast will be based on ‘loosely coupled account links’ to create ‘controllable anonymity’. This means that unlike the traditional e-payment systems where money strictly moves between two accounts, in the case of CBDC, transactional reliance on accounts is significantly reduced. Also, under this system, digital renminbi will be transferable from one e-wallet to another without using a bank account.

As of May, an internal testing trial was kicked-off at state-owned banks in four Chinese cities of Shenzhen, Suzhou, Chengdu and Xiong’an. In Suzhou, the digital renminbi is being used for paying salaries to some public servants, while in others, the trial has focused on food and retail level payments leveraging existing payment infrastructure of Alipay and WeChat Pay with a combined user base of more than one billion.

Patrick Hess, Finance Professor at Goethe University and Principal Supervisor at European Central Bank – Single Supervisory Mechanism, and a keen observer of China financial infrastructure development said that growing geopolitical frictions and uncertainties have led to increased use of the Chinese currency in direct bilateral trade settlement, especially in the energy market. He also observed that European countries are further away from a CBDC than China.

“The PBOC is trying to manage expectations and say this is not something that will happen next year. My guess is we will see the first CBDC issued in China in the next three years - building on China’s already quite advanced infrastructure such as Alipay and WeChat Pay”.

The long way forward

Research indicates that CBDCs do reduce or eliminate concerns around financial stability, consumer data privacy and payment system efficiency. However, before CBDCs inch closer to become a reality, several spots remain in the dark. The very underlying technology for instance could expose the whole financial system to cyber risks, hence technology preparedness from a new payment infrastructure perspective is key.

IMF research also points to possible disintermediation of the commercial banking system from an interest-bearing CBDC. As retail deposits move to CBDC holdings, this may force banks to raise deposit rates and charge higher rates on loans, or access more expensive and volatile wholesale funding channels, eventually weighing on banks’ profitability. The issue that should CBDCs be made directly accessible to public by a central bank or distributed by commercial banks remains unresolved as it depends on multiple dimensions and there is no single answer. “As financial infrastructures differ from one country to another, ultimately the impact must be measured on their respective functioning of monetary policy and financial stability”, commented Coeuré. DBS report on digital currencies noted that “initiatives to create multi-tiered CBDCs aimed at balancing the need for digital currencies against the risk of disintermediating the banking system”.

Broadly speaking, there is no firm consensus yet on the universal adoption of CBDCs as most projects represent stages of conceptualisation. Finally, the ultimate demand for CBDC will depend on the alternatives to CBDC such as the take-up of faster payment networks, especially when it comes to the implementation of transfers. “The answer in theory would be whatever is faster, efficient and cost effective, and it doesn’t necessarily need to be a CBDC. Countries with fast retail payment systems and reliable national ID systems have managed direct transfers very well”, concluded Shin.

And on that count, China appears to be ahead.

All Comments